Warnings on the Use of Transmissometer Data to Analyze Long-Term Visibility Trends

John Molenar

Air Resource Specialists, Inc., 1901 Sharp Point Drive,

Suite E

Fort Collins, CO 80525

December 12, 2002

The IMPROVE monitoring network currently operates 17 transmissometers at 15 Class I areas collecting estimates of light extinction. Most of these sites contain more than 10 years of data and it is tempting to use these data to examine the long term trends of haze. However, transmissometers are subject to varying biases that can obscure or worse, create false trends. In addition, the transmissometer data released on the IMPROVE website are at Level 1 of the quality control process and should be considered as preliminary data. These data should only be used after careful scrutiny and reconciliation with concurrent aerosol and nephelometers data. Due to the uncertainties in the transmissometer data, they have not been used historically for trend analysis, but as an adjunct data set to be used in an attempt to come to “closure” with aerosol and other optical measurements

Following are the main, but not all, issues related to the use of transmissometer extinction data. The misleading interpretations in the trends of haze that these transmissometer data can cause are then illustrated using data from Big Bend and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks.

Transmissometer Data Quality Issues

First: Transmissometers DO NOT directly measure the atmospheric extinction coefficient. A transmissometer measures the irradiance (Ir) of a light at some distance (r) from the source. The average extinction (bext) of the path is calculated as:

bext = ln (IO / Ir) / r (1)

where: IO is the estimated irradiance of the light source that would be measured at the distance (r) in the complete absence of any atmosphere (gases or aerosols).

Anything that modulates the measured irradiance (Ir) will affect the estimated extinction coefficient. Besides aerosols and absorbing gases along the path, this can include (but is not limited to): snow, rain, fog, clouds, airborne insect swarms, birds, fogged or dirty optical surfaces, misalignment of the detector or light source, optical blooming or turbulence, non‑uniform light beam, or varying IO.

Second: Transmissometers CANNOT be directly calibrated. Various methods have been used to indirectly estimate IO but they all include major uncertainties and are not always self‑consistent. In addition to the uncertainties associated with the initial estimate of IO, current transmissometers occasionally suffer from step changes in the initial IO when lamps are replaced in the field and all experience an increase in IO as the lamp ages. It must be noted that any % change in IO results in an absolute incremental offset in calculated bext that is independent of bext. For example: a transmissometer operating along a 5km path that has an unaccounted for 5% change in IO will have an absolute offset of 10 Mm-1 in calculated bext for all bext.

Third: “Validity” codes are assigned for every hourly bext measurement using standard defined criteria in an initial systematic effort to identify possible “interferences” and apply standard corrections to account for IO drifts that may be biasing the data. These procedures are very global and at best should only be considered the first task of a series of increasingly more comprehensive data validation methodology.

Fourth: Primarily due to the above concerns, relying on transmissometer data without examining concurrent co-located nephelometer and/or speciated aerosol data is dangerous often leading to misleading conclusions. Each specific site must be critically examined using all concurrent nephelometer and aerosol data before any confidence can be placed in the transmissometer data.

Example Using Analysis of Big Bend and Guadalupe Mts. Transmissometer Data:

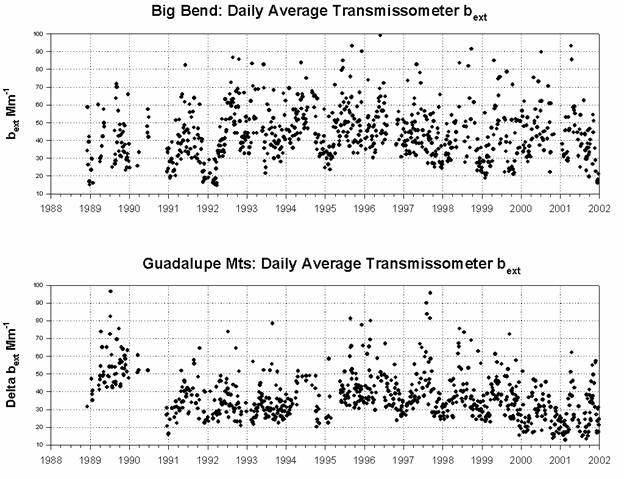

The misleading conclusions that can result from not reconciling transmissometer and aerosol data is illustrated in the Big Bend and Guadalupe Mts. IMPROVE data. Figure 1 is a timeline of daily average bext from transmissometer measurements at the two sites for IMPROVE aerosol sampling days. The daily average is only plotted if a minimum of 12 hourly non-flagged transmissometer bext values are present. Examining these bext trends it appears that bext decreased significantly at Guadalupe Mts. between 1989 and 1991. At Big Bend it appears that bext increased from 1989-1994 and has been decreasing since then. These trends are quite apparent when looking only at the transmissometer data, however, when they are compared to simultaneous speciated aerosol data a much different picture emerges.

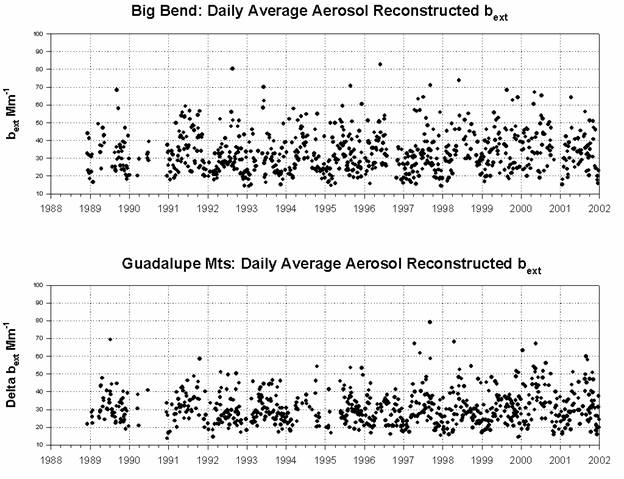

Figure 2 plots the daily reconstructed aerosol bext calculated from the IMPROVE speciated aerosol data using the IMPROVE extinction equation:

bext = 3.0 f(rh) [Sulfate] + 3.0 f(rh) [Nitrate] + (2)

4.0[OMC] + 1.0[Soil] + 0.6[Coarse Mass] +

10.0[LAC] + 10.0

The daily f(rh) employed is the average of all hourly f(rh) calculated from measured onsite hourly relative humidity data that corresponds to the bext hours used in the average bext calculation. The trends seen in the transmissometer bext plots are NOT apparent in the reconstructed aerosol bext plots.

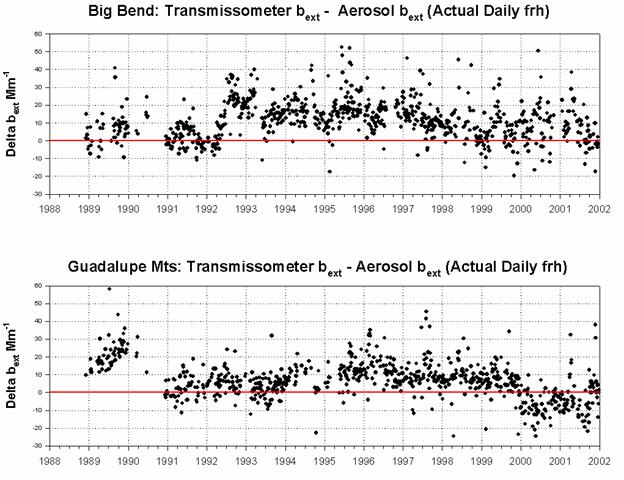

Figure 3 plots the difference between concurrent daily average transmissometer bext and daily reconstructed bext from speciated aerosol data at Big Bend and Guadalupe Mts. National Parks for the period 1989 – 2001. Examination of the plots shows:

- There are significant, frequent, and varying in intensity, offsets in delta bext at both sites.

- Guadalupe Mts. has a significant offset in delta bext from 1989 – 1991, which corresponds to the decreasing light extinction at Guadalupe Mts. as measured by the transmissometer.

- Trends at Big Bend are also associated with offsets in delta bext timeline.

Two possibilities that would describe the timelines presented in Figures 1-3 are: (1) the transmissometer data is correct and some mechanism is causing multiple rapidly varying incremental changes in the speciated aerosol data; or (2) the speciated aerosol data is reasonably consistent and errors in estimates of IO are causing these step functions.

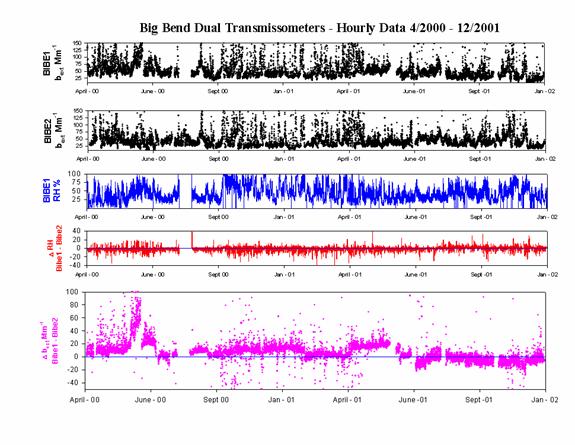

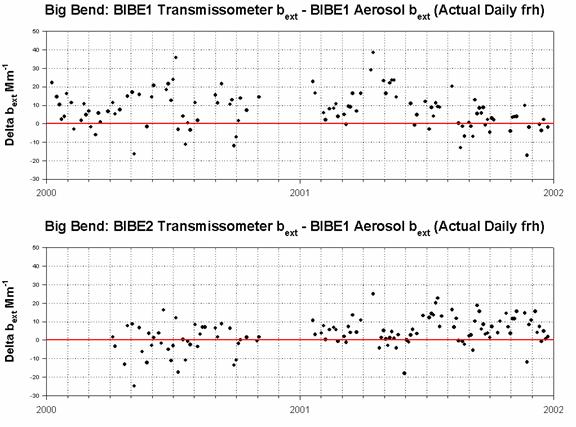

To investigate this issue a second transmissometer was installed at Big Bend in 2000 operating along the same path as the existing system, but about 30 m higher above the surface. Figure 4 plots various analyses of the dual Big Bend transmissometers. The same rapid, varying in intensity offsets are seen in the delta bext between the two transmissometers as seen in the transmissometer-aerosol delta bext in Figure 3.

Figure 5 presents the difference between concurrent daily average transmissometer bext and daily reconstructed bext from speciated aerosol data for the dual Big Bend transmissometers (same analysis as Figure 3). For 2000 and the first half of 2001 the new BIBE2 system agrees better with reconstructed aerosol bext than the original BIBE1 system. After mid-2001, the agreement is reversed.

Conclusion

This brief example emphasizes the extreme care that must be taken when using only transmissometer data in long-term trend analyses. It is quite clear that relying only on transmissometer data without examining concurrent co-located nephelometer and/or speciated aerosol data is dangerous often will lead to misleading conclusions. Each specific site must be critically examined using all concurrent nephelometer and aerosol data before any confidence can be placed in the transmissometer data.

Figure 1: Daily average transmissometer bext timeline at Big Bend and Guadalupe Mts. National Parks 1988 – 2001 for IMPROVE aerosol sampling days. Daily average bext has a minimum of 12 hourly non-flagged transmissometer bext values.

Figure 2: Daily average aerosol reconstructed bext timeline at Big Bend and Guadalupe Mts. National Parks 1988 – 2001. Aerosol bext is calculated using the IMPROVE algorithm. The daily f(rh) employed is the average of all hourly f(rh) calculated from measured onsite hourly relative humidity data that corresponds to the bext hours used in the average bext calculation.

Figure 3: Daily delta bext (transmissometer bext – aerosol bext) timeline at Big Bend and Guadalupe Mts. National Parks 1988 – 2001. Daily average bext has a minimum of 12 hourly non-flagged transmissometer bext values. Aerosol bext is calculated using the IMPROVE algorithm. The daily f(rh) employed is the average of all hourly f(rh) calculated from measured onsite hourly relative humidity data that corresponds to the bext hours used in the average bext calculation.

Figure 4: Hourly transmissometer bext data for Big Bend National Park dual transmissometer experiment. BIBE1 is the original system. BIBE2 operates along the same path length only about 30 m higher above the surface.

Figure 5: Daily delta bext (transmissometer bext – aerosol bext) timeline at Big Bend National Park 2000 – 2001 for the dual transmissometers (BIBE1 and BIBE2). Daily average bext has a minimum of 12 hourly non-flagged transmissometer bext values. Aerosol bext is calculated using the IMPROVE algorithm. The daily f(rh) employed is the average of all hourly f(rh) calculated from measured onsite hourly relative humidity data that corresponds to the bext hours used in the average bext calculation.